Seven Architectural Decision Making Fallacies (and Ways Around Them)

(Updated: )Reading time: 8 minutes

Content Outline

When making Architectural Decisions (ADs), things can go wrong. Biases and misconceptions are common. As a result, answers to “why this design?” questions, captured in AD Records (ADRs), may have little to do with the actual product requirements and project context. Project/product success is at risk in that case.

Let’s review some common fallacies and find ways to counter them.

Motivating example

You might have come across ADs whose ADRs read as this:

“We will build our online shop as a set of microservices because our cloud provider does that successfully in its infrastructure. They also provide a reference architecture for this variant of SOA, a de-facto standard for modern enterprise applications.”

Sounds great, right? Well, at least three fallacies are in action here. Let’s find out which ones.

How to get it wrong: seven decision making fallacies

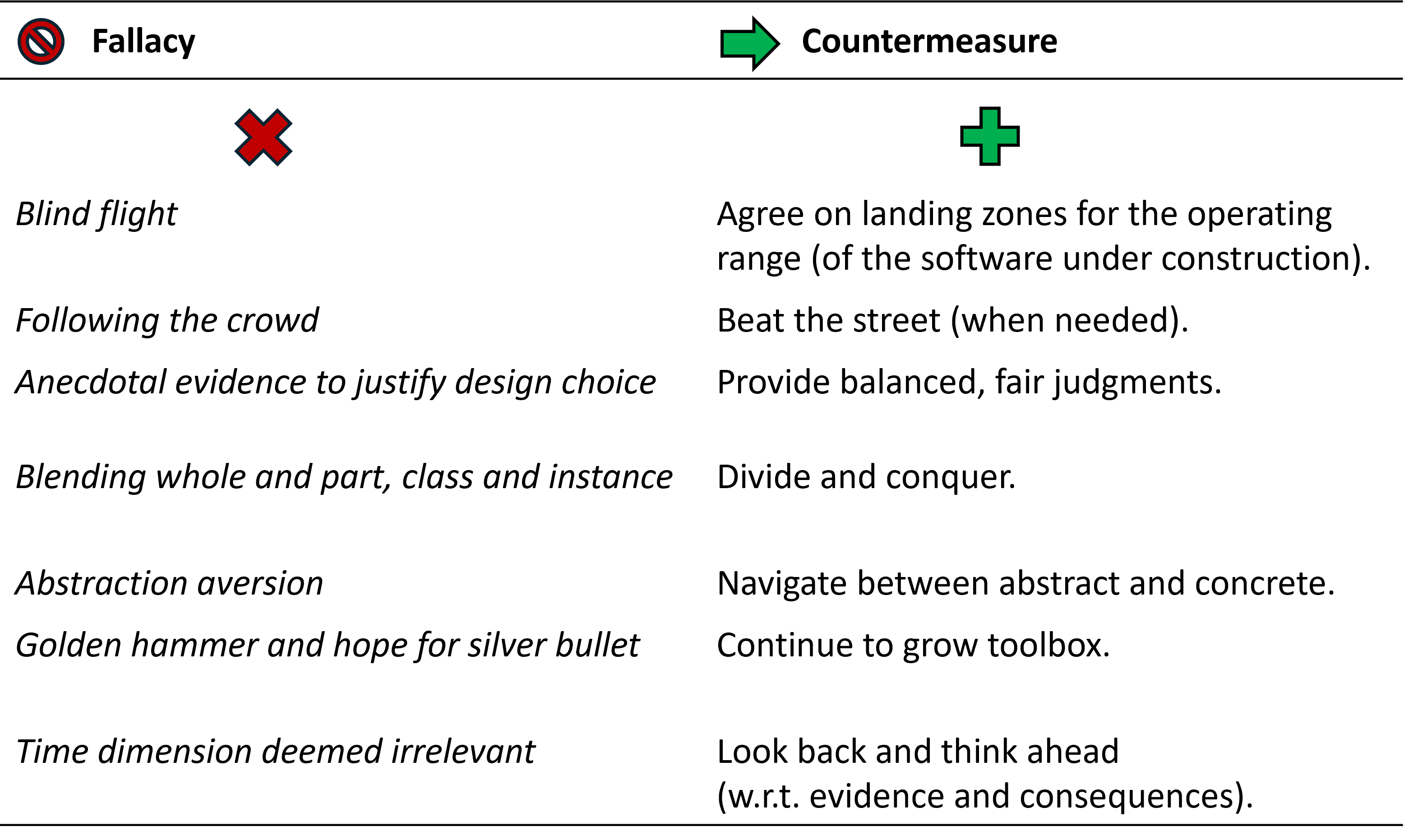

The following seven recipes for making ADs form a definite “not-to-do-list” (I moved examples and details to footnotes1 to keep the list short and concise; countermeasures follow in a subsequent list):

- Blind flight. Skip context modeling and requirements analysis. Do not bother to elicit Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs), do not waste time to make high-level quality goals specific and measurable. Who wants to find out whether a particular NFR (“-ility”) is achieved anyway?2

- Following the crowd. Rest assured that what works for others will work for you too, no matter what the requirements might be. Numbers matter, big is beautiful! This fallacy of relevance is also known as lemming effect or argumentum ad populum.3

- Anecdotal evidence to justify a design choice. Find a positive or a negative example in tribal knowledge and base your entire argumentation on it. Success or failure on one single project in the past, for instance reported in a blog post with a clickbait title, certainly implies that future usages will have the same outcome (good or bad).4

- Blending whole and part, or class and instance. Everything is related. If one concept in an architectural style has a bad reputation, the entire style must be bad and ought to be neglected. If one pattern from a pattern language does not fit, the entire language must be banned. This reasoning works in the other direction too: if one concept fits, everything else in a style or pattern language must be good too.5

- Abstraction aversion. Do not ask which concrete instance of a more general problem you are facing; abstractions bring indirection with them, which wastes resources. Decide for concepts, technologies and products/services at the same time and create a single mashup ADR.6

- Golden hammer and hope for a silver bullet. One size fits all. Searching for alternatives is wasteful; relevant candidate solutions find their problems, they do not have to be searched for. Eventually, a breakthrough innovation will improve productivity, reliability and simplicity so much that AD making becomes trivial or even obsolete.7

- Time dimension deemed irrelevant. Once some evidence about a design option has been found, keep on using it to justify future AD choices; Information Technology (IT) is a stable domain with few if any innovations after all. Hence, application architectures do not drift, and designs do not erode over the years.8

🤔 Which of these fallacies shine through in the shop example from the start of the post? I found three (and it would be pretty easy to extend the example to feature the remaining ones as well).

Bonus fallacy: AI über-confidence

A new contestant has entered the playing field — blind faith or über-confidence in Artificial Intelligence (AI). The AI hype train rides at full speed at present, with destination unknown:

- While AI assistants have their place and promising use cases (e.g., “vibe architecting”), usage of generated design advice without quality assurance is an element of risk; accountability is an issue.

- Prompts have their role to play — if you bake one or more of the above fallacies into your prompt, what do you expect a stochastic parrot to reply that has been trained on trustworthy sources but also on known uses of the fallacies?

- “More Resources about AI You Might Want to Review” and Ten “Resources about AI in Software Engineering You Do Not Want to Miss” point at articles and presentations that contribute to the discussion.

Would Sorcerer’s Apprentice be an appropriate alias name for this new fallacy? 🤔 9

How to get it right: from poor to proper ADs and ADRs

Now that we have seen what not to do, what should we do instead?

Let’s revisit and counter the seven fallacies one by one.

- Agree on landing zones for the operating range of the software under construction. Never forget that requirements and context matter; make the context explicit and compare it with that on previous projects. Use it to elicit specific and measurable NFRs.10

- Beat the street (when needed). Reusing the solution to a different problem without checking whether the requirements are compatible is a decision making smell, and market or technology community trends alone are bad scouts. Apply a recognized method or your own heuristics when transitioning from analysis to design.11

- Provide balanced, fair judgments. Use SMART NFRs, elicited when following advice item 1, as criteria justifying your ADs in ADRs. Make tradeoffs and confidence levels explicit. It is ok to blend in gut feeling; some bias is unavoidable in “big” decisions. However, Résumé-Driven Development is an anti-pattern.

- Divide and conquer. Be clear about the scope you operate on; do not mix system-wide arguments with local ones in a single ADR. Once an evolvable overall structure is in place (system-wide, “big” decision), follow-on decisions can address more local, component-specific concerns. Practice divide-and-conquer both in the problem space and in the solution space; when deciding for a style or pattern language, it is perfectly fine to leave out certain style elements or pick only one part or pattern.

- Navigate between abstract and concrete. To get abstraction levels right, look for is-a relationships in data, but also in capabilities. Going back and forth (or up and down) often is required when establishing is-a relationships. When evaluating AD options, make sure you are not comparing carrots with parrots (or carrots with animals and vehicles or other things). This might sound obvious (and it might be initially); however, over time abstraction-refinement violations do creep in. Distinguish abstract, conceptual arguments from concrete, technological ones; both types have their place but should fit the type of decision made. Pattern sections and technology or product/service choices, for instance, should to go separate (but related) ADRs.

- Continue to grow your architecture toolbox. They say that every problem looks like a nail if the only tool you know is the hammer. Stay curious and open-minded, and try new practices, patterns and tools. Reflect, research, and discuss them. Interact with and learn from other architects and developers.12

- Look back and think ahead. Make the expected lifecycle of the architecture and the system under construction explicit, e.g., disposable or durable. Specify a review due date for early ADs. For durable systems, add a time dimension to the discussion of consequences in the ADR. Repeat and update older technical evaluations such as performance measurements to reproduce their results before using them as arguments.13

Look for instances of the not-to-do-list entries in architecture, design and code reviews.14 Find ways around them; avoiding big mistakes will pay off in the long run.

Fallacies and biases beyond IT and software architecture

My “How to get it wrong” collection contains software design domain-specific versions of more general fallacies and biases, as investigated by psychologists and economists. Some examples are:

The Logically Fallacious website has more. General advice about these fallacies and biases is applicable to AD making too, with adequate abstraction-refinement navigation in place.

Here is some additional, more general advice:

- Don’t let the circumstances or loudmouths push you around. Invest in analysis time and building consensus.

- Identify ADs proactively, make them consciously, document them as ADRs durably. Acknowledge those who contributed to the AD making.

- Be aware of the cognitive load of chosen options, assess the cost of building, owning, changing and be aware of the risk of over-architecting.15

- Apply technology for its intended and recommended use, generative AI in particular.

- Talk to peers about all of this; AD making is a team sport. Group decision making mitigates the risk of falling for a fallacy. For instance, a well-organized architecture board can unleash collective genius.

Nobody is perfect; biases are human. Still, your architecture and its stakeholders will appreciate that you catch and fix as many fallacies as possible — or avoid them in the first place.

Further reading

Online resources helpful for fallacy spotting (and/or avoiding them in the first place) include:

- Learn about the importance of context from Eltjo Poort in “Architecture is Context”.

- Check out good decision making and software architecture design practices collected by Ruth Malan in “Architecture Clues: Heuristics, Part ii. Decisions and Change”.

- Ride the IT Architect Elevator with Gregor Hohpe.

- Listen to “Controlling Your Architecture with Philippe Kruchten”, The Azure DevOps Podcast, ep.195

- Get an academic view in “Decision-Making Techniques for Software Architecture Design: A Comparative Survey”.

Which fallacies and cognitive biases have you come across when making architecture decisions?

– Olaf16

Editorial information: No AI was used to write this post.

End notes: examples and background information

-

The not-do-to presentation style of this post is inspired by a book by Rolf Dobelli (and others). Moving details and examples to footnotes is not Dobellian as far as I can tell. 😉 ↩

-

Operating range mismatches may exist, previous usage and experience often differs from current wants and needs. Underspecification gets you in the long run. Overspecification is harmful too; it is tempting to believe that the current requirements are extraordinarily special, sometimes more special than they actually are. This effect is known as Big Tech (or FAANG) envy. ↩

-

Variations include conference euphoria, guru seduction (aka “influentia”), tunnel vision (“I have always done it like that”) and narcissism (“there is only one way: my way”). ↩

-

Technology promoters often use these singletons to make the case for the latest fad; even books oversimplify option comparisons sometimes. Example: Just because several SOA projects failed due to Enterprise Service Bus (ESB) misuse or other design smells (see this paper), the architectural style as such does not have a scalability or reliability problem. Same for microservices, by the way: I can easily come up with a component diagram featuring a microservices architecture that scales poorly because of excessive bounded context decomposition and service communication. 😉 ↩

-

Example 1: The term “REST API” typically is neither accurate (when the particular constraints of the REST style are ignored) nor complete (protocol information missing: often but not necessarily HTTP). Example 2: The ESB pattern, service registries and dynamic service matchmaking are optional elements of the SOA style, not defining ones (see this post); the mandatory service contract pattern still makes sense even if the optional style elements do not fit. By the way, well-designed messaging channels have always been thin; message transformations and routing are the only forms of logic that make sense in an ESB. Who would place complex business logic such as workflows or domain model implementations in an integration middleware and call that a style? 🤔 ↩

-

Examples of abstract concepts compared with concrete technologies supporting other concepts: REST (HATEOAS etc.) vs. SOAP over HTTP, binary data transfer vs. JSON document exchange, relational database management vs. MongoDB. Mixing class and instance level does not make much sense. How would you receive a comparison such as “A Granny Smith apple is healthier than milk”? Rather compare apples with milk or Golden Delicious apples with Granny Smith apples. ↩

-

If you are wondering where the silver bullet metaphor comes from, check out this blog post. ↩

-

Some might say that older technical information and advice should not be dissed as obsolete but cherished as precious. Really? Counter-example 1: A performance evaluation and comparison from last year might be obsolete by now, for instance with a new release of a library or product or service. Counter-example 2: A company takeover might change the odds of a software product to preserve its characteristics and stay vital in the long run. ↩

-

With a parrot takes the place of the broom in the poem. 🤩 ↩

-

Context dimensions include size, criticality, business model, rate of change and team distribution (among others). ↩

-

Attribute-Driven Design (ADD) is one option. Our Design Practice Repository (DPR) has an AD making and capturing activity and also features SMART NFR elicitation. ↩

-

From technical sales people too, at least those not relying on magic sales tricks. 😂 Sample trick: Start a presentation with an artificial enemy everybody easily agrees on, e.g., the waterfall model. But waterfall was not the only way or the mainstream before Agile; the Unified Process, for instance, is iterative and incremental — and older. ↩

-

“How to create Architectural Decision Records (ADRs) — and how not to” features more patterns and anti-patterns for ADR creation. ↩

-

“How to review Architectural Decision Records (ADRs) — and how not to” discusses good review practices. ↩

-

You can have the best intentions, pick the right concepts… and still fail when implementing them poorly. This speaks badly of the implementation, not the concepts. ↩

-

Stefan Kapferer, Cesare Pautasso, Gerald Reif, Mirko Stocker, Tobias Unger and Hagen Voelzer commented on earilier versions of this post and suggested additional fallacies, variants of the presented ones and examples for them. 🙏 ↩